Tor Project - Anonymity Online

InfosecMost network admins will come across Tor at some point in their career. It’s a great piece of software, symbolising personal freedom and security for everyone on Earth, but a sad part of most network admin jobs is that we often get asked to block it.

Going against the free nature of most Internet guru’s, it’s still something that is required from time to time. Tor themselves understand and respect this as mentioned in the FAQ:

If people want to block us, we believe that they should be allowed to do so. Obviously, we would prefer for everybody to allow Tor users to connect to them, but people have the right to decide who their services should allow connections from, and if they want to block anonymous users, they can.

If you own a network serving your own needs, you are entitled to control its content (that doesn’t include you, ISP’s!), it’s grey area for your users’ personal privacy vs. ownership, - but we’ll leave that debate for the philosophers for now. In the meantime, I’ve decided to provide advice on how to reduce the chances of Tor on your own local network, whether it is a corporate office, a school or other locked down environment. I say reduce because if you wish to allow HTTP\HTTPS traffic, there’s a chance Tor will get through. It requires a multi-layered approach if you wish to effectively block Tor.

I’d like to my position as clear as possible. Tor is a good thing. It’s helped liberate people all over the world from authorities who believed they knew better. In fact, it’s such a good thing for the Internet, I’ve also provided details on how you can help, and run your very own Tor relay, found here.

Tor comes in many shapes and sizes, it support Windows, Mac, Linux and even Android for smartphones. If you’re in control of the entire network and the client devices on it, you can reduce Tor usage using a two-layered approach to security.

Layer One - Device Security

The first step – ensure clients cannot run executables you haven’t personally sanctioned. Tor runs as an executable and also starts its own SOCKS service on the local PC. Applications requiring the use of Tor connect to the local application, which SOCKSify’s the request into the Tor network – there’s already several ways you can prevent this process if you physically have control over the PC. Tor and other projects (such as Tails) can also run from Live CD’s or USB sticks, so ensure these devices are off limits. Specifically:

Windows

Tor’s behaviour on Windows is a little more predicable for now. The SOCKS server will start listening on port 9050, so you can simply use the built in Firewall to prevent the Tor executable from binding to this port, or making any connections whatsoever. In fact the Windows Firewall can explicitly deny the application. You can also use Group Policy to ensure users cannot run the executable; ensuring traffic cannot reach Tor.

OSX

MAC clients using the Tor bundle may find that the SOCKS port used by Tor is random, but the Tor port in a standalone installation should still be 9050. This makes it hard to block each time, so you’ll simply need to ensure applications cannot be run without prior permission. Like Windows, ensure the machine cannot run applications without permission.

Layer one is easy if you own the devices, but in many cases – you only have control over the network, and the devices are off limits to you. This means only your network devices can help. For this – you’ll need a device which can work at higher levels of the OSI model.

Layer Two – Network Security

Tor is very clever at finding a path to the Tor network. It’s capable of connecting to its directory servers using a variety of ports – all encrypted, however the initial installation is only aware of eight servers which act as authoritative directory servers, though blocking these will slow Tor down – it will not stop it.

Tor can even fall back to simply using the common HTTP\HTTPS ports 80 and 443. Most networks allow these, and therefore you’ll have to perform protocol inspection to confirm the traffic really is HTTP\HTTPS.

In the event Tor is unable to contact any of its default directory IP’s, it will fail to connect. It almost sounds like you’ve won the battle - however Tor can then be configured to use any directory IP’s your able to provide. These will typically be ‘bridge relays’, or bridges for short – they do not exist in the public directory, making them very difficult to categorise and block. These can be provided from the web, or via email (to get a list of bridges near you, visit https://bridges.torproject.org/). Blocking this URL will help prevent most users finding their own bridge. But the IP’s can simply be recorded elsewhere and stored for later use.

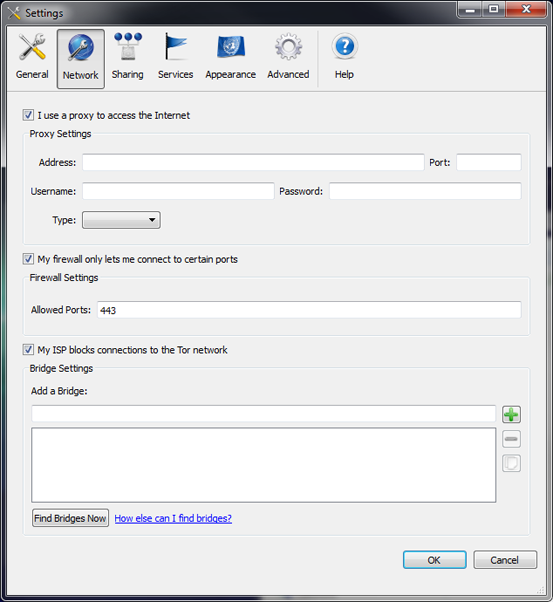

To understand this process, let’s use Vidalia – the graphical front end to Tor, to take a look at Tor’s connection settings:

Vidalia provides three proactive methods to get onto the Tor network. The first is the typical proxy settings, should only the proxies have Internet access – users will be forced to use this setting, allowing finer control over Tor.

The second is ‘My firewall only lets me connect to certain ports’. This option restricts the outbound directory requests to the IP’s listed, in case a firewall only allows common ports. Most Tor users will check this when on corporate\education networks.

Finally, ‘My ISP blocks connections to the Tor network’ allow you to enter unpublished bridge IP’s. ISP’s can choose to block the known directory IP’s (though we know few who do). With this setting, you can find your own bridges to connect to. Using this option may slow down Tor, but will still allow it to work.

Tor Outbound

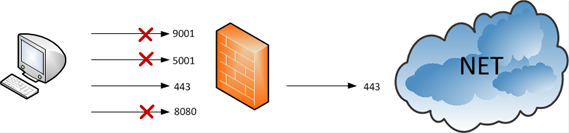

Tor uses the same ports\protocol to learn of nodes and to connect to them. It connects using a multitude of ports, including port 443, 80, 9001, 5001 and 9090. Users can use the second option listed above to fine tune this process if they know which ports their network allows.

To effectively control Tor – you either need to block the ports it attempts to use, or perform protocol inspection on the ports it can use. Obviously blocking all ports wouldn’t provide much use to the rest of your applications, so the best approach is to limit the amount of available ports.

Firewall to the rescue. These devices excel at blocking things. On the stricter end of the scale, let’s see a firewall which only allows the common HTTP\HTTPS protocol:

Tor easily got through by correctly guessing the HTTPS port was open. In fact, if clients know what ports are open, they can save Tor from guessing by adding the ports to the configuration under ‘My firewall only lets me connect to certain ports’. Alternatively the ‘torrc’ file can be edited with:

FascistFirewall 1

ReachableAddresses *:443

These settings will instruct Tor to only use port 443 for outbound.

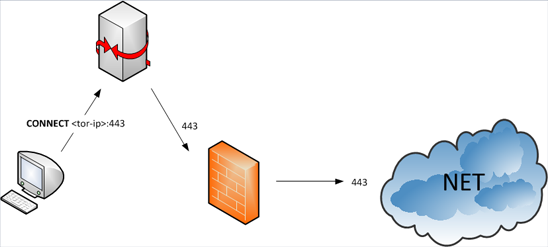

But what if you use a proxy for centralised Internet access? Can Tor still connect? Yes. Tor can be configured with a proxy; however it will still use its own SSL to communicate, so protocol aware proxies can take care of this. The following shows a dump proxy configuration:

Tor sends a HTTP CONNECT request to the proxy, which simply opens the connection for Tor. SSL communication begins and Tor has connected successfully.

Protocol Inspection

How do we prevent the proxy or firewall from blindly allowing Tor to connect to its nodes? We have to ensure the traffic is legitimate SSL, one way we can determine its not – is to validate the certificate.

Tor nodes exchange certificates like any other SSL transaction. However since the certificates are dynamically generated for each Tor node, they are not signed by a certificate authority (CA). This means protocol aware devices which understand SSL can block them.

Proxies such as Squid and Blue Coat are capable of detecting this, and can be used to block Tor connections. Firewalls have virtually no support for SSL inspection (except a small few), so they are only good for blocking ports. To effectively block Tor on your network, you’ll need to utilise protocol inspection in some form.